911 Professional Career and Supports

Introduction

911 professionals[1]—the operators, call takers, call handlers, and dispatchers in Emergency Communications Centers (ECCs) [2] throughout the United States—collectively respond to an enormous call load, estimated at 240 million calls annually.[3] This workload has increased considerably in recent years, with over half of all ECCs surveyed in 2017 reporting an uptick in the number of dispatched calls.[4] Staffing has not kept pace with increased demand for emergency services, [5] which has further spiked during the COVID-19 pandemic.[6] Much is asked of these 911 professionals, who are tasked with supporting people who are seeking information and guidance, navigating problems and conflicts, and experiencing crises and victimizations, often collecting information from a frightened or confused caller in a short conversation. With each incoming call, 911 professionals must be prepared to pivot to meet the needs of the caller. This may involve patiently assisting a senior experiencing problems with medication, calming a distressed mother whose tween has yet to return home from school, or responding empathetically to a traumatized victim of violence. Each call requires a different set of strategies. Regardless of the nature of the call, each one can be stressful from the perspective of the 911 professional and can be life-changing from the perspective of the caller and others.

In essence, 911 professionals are America’s true first responders, serving as gatekeepers to law enforcement, fire, and emergency medical services (EMS) responses to community calls for service, and applying their best judgment to discern the appropriate response. 911 professionals are required to understand and comply with a wide array of policies for how to handle specific call types. They also have a critical role in preparing responders—particularly police officers—to arrive on the scene in a manner that protects their safety without predisposing them to approach difficult events in a way that reflects implicit or explicit biases or aggravates the risk that responders will use excessive force. 911 professionals may also be able to reduce reliance on law enforcement, dispatching responses from social workers or mental health clinicians instead of police officers when appropriate.

This chapter describes the various roles 911 professionals play, with a focus primarily on those whose work includes interacting with police dispatchers and responders. After describing the current landscape of 911 professional recruitment, training, and retention, the research evidence on these topics as well as the job satisfaction and degree of stress experienced by 911 professionals is presented. The research questions at the end of this chapter put forth several important areas of inquiry that can inform strategies to improve the experiences and effectiveness of 911 professionals.

Types of 911 Professionals

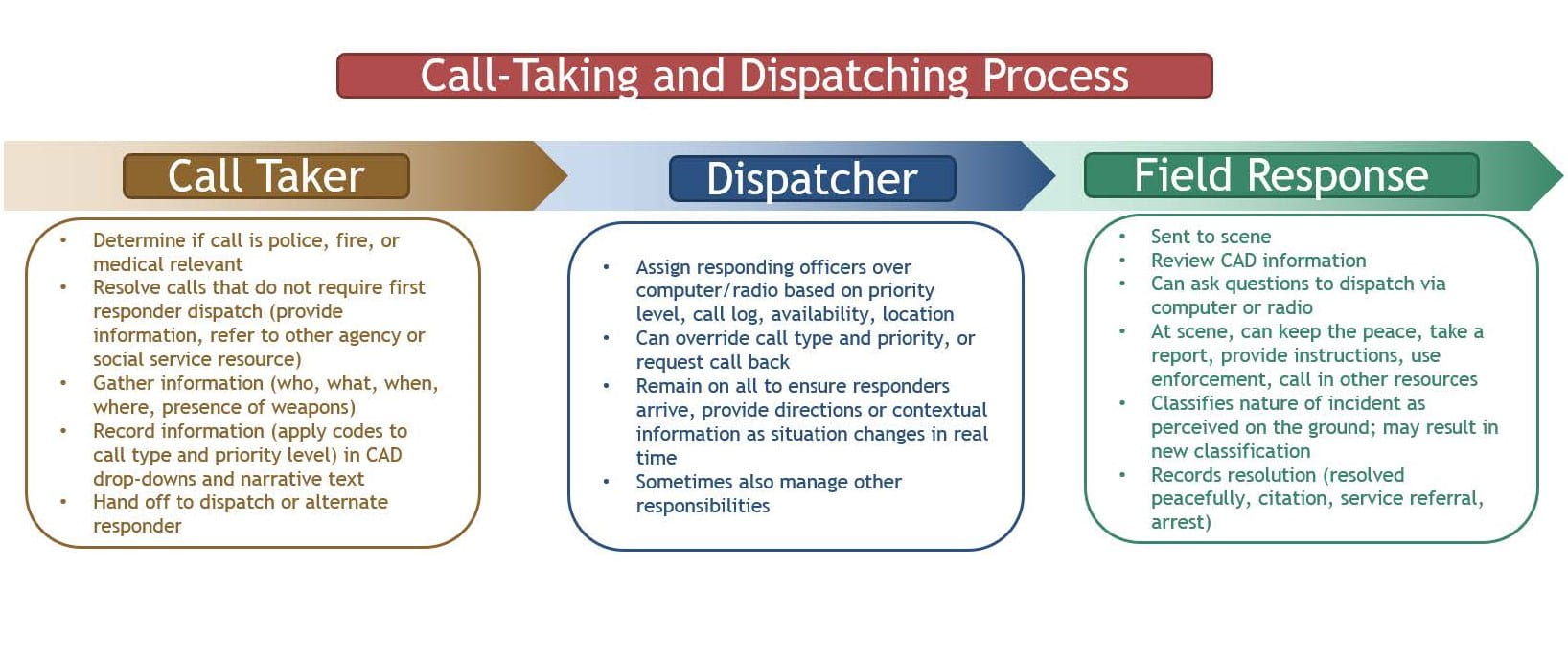

Figure 1.1: Call-Taking and Dispatching Process

Call takers, also known as call handlers, telecommunicators, or operators in some locations, receive public requests for assistance via phone call, text message, or alarm system alert. Call takers assess the reason for and exigent nature of each call. They may resolve the call on their own by providing information or guidance to the caller, or they may refer it to a dispatcher or to another information or resource line. Recent research on the largest ECCs in the country found that call takers resolved half of all calls without having to refer to dispatch, by engaging in informal counseling and problem solving.[7] They also resolved one third of calls pertaining to property crimes and disorders that were not vice-related, and 22 percent of traffic-related calls.[8] As such, call takers play a critical role in diverting calls from police response.[9]

Dispatchers direct field responders to crime scenes and other incident sites, and provide crucial information about the context of the event and any changing dynamics that unfold until responders arrive and the issue is resolved. Dispatchers communicate with and monitor the progress of emergency unit responders and provide instructions, such as first aid advice and how to remain safe, to the caller until the response unit arrives.[10] In larger call centers, the roles of call taker and dispatcher are distinct and represent a career progression, whereas in smaller call centers one individual may serve in both roles owing to limited staff resources.[11]

While the job of 911 professional is occupationally categorized as administrative,[12] this designation misrepresents the true nature of this work. Studies have documented the complex and challenging nature of 911 jobs, which require strong communication skills, nuanced judgments, the technical literacy to interact with computer-aided dispatch systems, and the ability to faithfully comply with a dizzying array of policies.[13] 911 professionals are tasked with navigating critical situations that, particularly in smaller call center service areas, may involve their own colleagues, friends, and family members as both callers in need and field responders.[14] Importantly, the way in which 911 professionals interpret and resolve calls has implications for how field responders perceive the level of risk and nature of the incident. These communications could predispose responders to behave in certain ways that, in the best-case scenario, support the safe and efficient resolution for all parties, or—in the worst case—inadvertently prompt unnecessary force or aggravate racial or other biases.[15] Indeed, studies examining the nature of exchanges between callers and 911 professionals suggest that these interactions may compromise decision-making on the part of both 911 professionals and officers.[16],[17],[18]

State of Practice

Prior to the 1968 establishment of 911, call takers and dispatchers handling emergency calls for service had little to no training.[19] The field was already populated primarily by women (referred to as the “feminization of dispatch”[20]) who were relegated as “complaint clerks” and lacked the authority to designate which calls warranted police response.[21] The rapid proliferation of 911[22] prompted the field to become more formalized in terms of training and professionalization, particularly in the area of emergency medical dispatch, as the recognition of the life-saving aspects of both effective triage and verbal guidance (also known as “pre-arrival instructions”) by 911 professionals grew.[23]

As technological advances in 911 have evolved, so too has the sophistication of the 911 profession. The establishment of Enhanced 911 (E911) in the mid-1970s brought with it selective routing and the ability to discern the location and phone number of the caller, with selective transfer and alternate routing soon following.[24] These features enabled ECCs to automate aspects of their triage and dispatching processes, and required 911 professionals to possess the skills needed to navigate the new software systems and complex decision trees that accompanied them.

The field has continued to evolve, aided in part by the development of call-taking standards. The National Emergency Number Association (NENA) developed customizable Law Enforcement Dispatch Guide cards[25] and the Association of Public Safety Communications Officials (APCO) offers triage protocols that draw from the 911 professionals’ experience and judgment.[26] Relatedly, the Advanced Medical Protocol Dispatch System developed by the International Academies of Emergency Dispatch is widely used by emergency medical service 911 professionals.[27]

Training certification and state training requirements have also enhanced the expertise of 911 professionals, who may be certified as emergency medical, fire, or police dispatchers, with some 911 professionals certified for two or all three of these roles.[28] Managers and supervisors can also obtain certification as emergency number professionals or certified public-safety executives.[29] Training requirements vary considerably by state and municipality, as does compensation. While APCO International provides minimum training standards for 911 professionals, along with training and technical assistance, compliance with these standards is optional. It is unclear what share of ECCs adopt these standards.

In a survey conducted in 2019, about three in four of the 48 reporting states and territories indicated statewide minimum training requirements for 911 professionals overall, an increase from two-thirds in 2018.[30] Just 44 percent indicated statewide minimum training standards specifically for police dispatch.[31] Even among states that have minimum training requirements, standards vary considerably. North Carolina, for example, mandates a minimum of 47 hours of training,[32] whereas California requires 120 hours of classroom setting before simulation and sit-along training can commence.[33]

911 professionals also report insufficient training and lack of available resources with which to divert calls related to mental health concerns. A recent survey of ECCs across 27 states found that few 911 professionals were trained in how to handle behavioral crisis calls – about one in five lacked specialized resources, such as behavioral health clinicians, crisis-trained 911 professionals or field responder staff, or mobile crisis units.[34]

Uneven certification requirements may explain the wide range of compensation for various 911 professional roles. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the median annual salary for public safety communicator was $43,290 in 2020.[35] However, the website ZipRecruiter illustrates the range of pay by geography, placing the average annual salary for a 911 dispatcher (a higher-level subcategory of 911 professionals) at $48,232, with a high of $53,650 in New York to a low of $35,408 in North Carolina.[36]

Issues of insufficient compensation collide with increases in calls for 911 and challenges in recruiting and retaining 911 professionals. BLS projects that the number of 911 professional jobs will grow by eight percent between 2020 and 2030.[37] Similarly, a 2017 study found that over half of all ECCs have experienced an increase in the number of dispatched calls, with all experiencing staffing challenges.[38] The report also noted the mounting issue of staff attrition, with an average 911 professional retention rate of only 71 percent. Study authors conjectured that recruitment is becoming more difficult given that millennials desire more flexible work hours and are less likely to trust governmental institutions.[39]

Efforts to reclassify 911 professionals from administrative staff to emergency responders could go a long way to further professionalize the field, increase pay equity, and attract new 911 professionals while retaining seasoned staff. However, efforts to lobby the Office of Management and Budget have been unsuccessful.[40] Related legislation passed the House of Representatives in 2019 but died in the Senate.[41] This reclassification bill was reintroduced in April 2021.[42]

Research Evidence

Attending to 911 professionals’ training, support, and needs is essential to promote public safety while minimizing unintended, harmful, and inequitable outcomes. The research evidence on this topic, while largely descriptive, pinpoints issues and challenges along with potential remedies.

Recruitment, Retention, and Training

Given increased demands for 911 services and continued staffing difficulties experienced by ECCs, research on recruitment, retention, and training is particularly important.

Recruitment and Retention

Academic studies of effective recruitment strategies for 911 professionals are virtually nonexistent. A 2017 APCO International survey of ECCs identified workplace flexibility, supervisor and coworker support, employee recognition, opportunities for promotion, and sufficient compensation as key factors in both recruitment and retention.[43]

Training

Apart from how to handle calls pertaining to cardiac arrest, the topic of 911 professional training has garnered scant research attention. A systematic review of 149 studies pertaining to emergency dispatch research unearthed just two studies of training program efficacy, one in Sweden[44] and the other in Belgium.[45] Both studies found that quality assurance processes improved dispatch outcomes; however, one focused solely on cardiac arrest calls, and both are decades old.[46]

Training is important to ensure that 911 professionals comply with triaging and dispatching protocols. There is, however, a tradeoff between fidelity and competence in such protocols. Overly rigid policies can inhibit the ability of 911 professionals to apply experience-informed judgment regarding appropriate response. A recent study found that while 911 professionals resolve a large share of calls without need for officer dispatch, their decision-making is constrained by policies that require them to forward certain calls to dispatch based on event code, and sometimes these policies are even automated within the CAD system.[47] On the other hand, a lack of training may lead some 911 professionals to interpret calls in an inappropriately alarmist manner that can signal to police responders that the incident is a higher public safety threat than it actually is.[48]

The types of calls that often require dispatch in accordance with ECC policies include domestic incidents, mental health concerns, and suspicious persons – many of the same call types that are associated with charges of excessive force and biased policing.[49] In some cases, a caller may demand and receive police response, even if that response conflicts with agency policy based on the nature of the event.[50] This is not to suggest that 911 professionals should be afforded full reign in deciding which calls to forward to dispatch. Even with the benefit of professional judgment, 911 professionals may interpret and communicate with callers and field responders in ways that negatively influence decisions surrounding whether an officer is dispatched and how the officer perceives the event.[51],[52],[53] This can produce misinterpretations of the level of risk and yield biased outcomes.[54],[55],[56] Training that employs concepts consistent with the tenets of procedural justice may effectively reduce these unintended outcomes,[57] but has not been subject to evaluation.

Job Satisfaction, Stress, and Resilience Factors

Surveys indicate that most 911 professionals take great pride in their work, reporting relatively high job satisfaction and “compassion satisfaction,” the positive feelings one derives from helping others.[58] That said, 911 professionals face significant job stresses owing to the nature of the role, with one survey finding that respondents were exposed to roughly three in four types of traumatic events during the course of their careers.[59],[60] 911 professionals are exposed to trauma on a daily basis,[61] and such exposure has been associated with compassion fatigue,[62] burnout, and secondary traumatic stress.[63] Other studies have found that stress levels and rates of post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSD) are higher among 911 professionals than among police officers or the general population,[64] with dispatchers who report low job satisfaction more likely to experience burnout.[65] Indeed, another study of 911 professionals found that they had greater rates of occupational burnout than members of the general public.[66]

Some stresses experienced by 911 professionals are likely born of the nature of shift work, which has been associated with a large array of mental and physical health risks including obesity, sleep disorders, diabetes, anxiety, depression, and cardiovascular disease.[67] The high vacancy rates in many ECCs can result in forced overtime, which may exacerbate these outcomes, creating disruptions in work routines and further compounding stress, compromising occupational wellness, and reducing retention. One study identified a rate of obesity among a sample of 911 professionals that was 50 percent higher than that of the general population, and identified a strong relationship between poor physical health and compromised mental health among 911 professionals.[68] Other research indicates that 911 professionals who felt over-extended had high levels of stress, and those who had greater abilities to recognize and process their stressful experiences and emotions had lower stress levels.[69]

911 professional positions are primarily held by women, who disproportionately operate as their households’ primarily caregivers, and may find both shift work and the nature of the job particularly stressful.[70] A survey of a convenience sample of 911 professionals nationwide, resulting in 103 respondents, found that work-family conflict—described as the degree to which demands at work conflict with demands at home—was a significant predictor of PTSD symptoms, and emphasized that employee-focused policies and supports are essential to preserving a healthy work-life balance.[71]

Questions for Inquiry and Action

The research on 911 professionals is extremely limited. It is focused primarily on emergency medical responders rather than police dispatchers, and is typically conducted in a single jurisdiction or ECC. Even the more rigorous dispatch studies are largely retrospective, given the difficulties in conducting randomized controlled trials in emergency-driven settings.[72] Research specific to 911 professionals is largely descriptive, suffers from small sample sizes, or is entirely qualitative.

There are similar evidence gaps regarding the relative merits and impacts of various call-taking protocols, training and certification processes, and quality assurance and performance measurement standards. These evidence gaps call for increased partnerships between researchers and ECC administrators and operations personnel to build a more robust knowledge base.[73]

Research questions that, if answered rigorously, would fill critical knowledge gaps include the following:

- To what extent do existing training opportunities meet the needs of both 911 professionals and the demands of the job? Why do some 911 professionals pursue in-service training opportunities while others do not? What is the impact of certification and training requirements on 911 professionals’ capabilities and job performance, particularly with regard to resolving calls on their own and adherence to triage and dispatching policies and protocols?

- What are the most effective recruitment and retention strategies for 911 professionals? How does the effectiveness of these strategies vary by age, sex, geography, and other factors?

- To what degree does reclassification of 911 professionals from administrative to first responder facilitate recruitment and retention, increased job satisfaction, pay equity, and improve retention rates?

- To what degree does reclassification of 911 professionals from administrative to first responder facilitate better outcomes for field responders and for people who are the subject of calls?

- What would be the budgetary impact—both for independent multi-jurisdiction ECCs and for public safety agencies that manage emergency calling services—of creating career and compensation parity for 911 professionals on par with those for field responders and public safety officers?

- What are the impacts of improvements to 911 professionals’ supervision, wellness supports and resources, and compensation levels on their job satisfaction, job performance, and tenure?

- To what degree does co-location of nurses, mental health clinicians, or social workers at ECCs facilitate safer and more effective safety and health outcomes for people in need?

- To what extent would increased community awareness of and access to behavioral health resources and supports allow 911 professionals to divert more calls from police response?

- What internal (e.g., personality, coping) and external (e.g., work conditions, shift) factors increase the likelihood of resilience among 911 professionals?

- What is the impact of training 911 professionals in implicit bias and procedurally-just interactions with members of the public as measured by rate of 911 professional call resolution, share of calls resulting in police dispatch, nature of police response, and public safety and wellness outcomes?

- What are the advantages and disadvantages of giving 911 professionals more agency to divert calls from police dispatch? What is the impact of such diversion on public safety outcomes, use of excessive force, racial disparate policing, and community trust in the police?

Notes

[1] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Outlook Handbook: Public Safety Telecommunicators,” accessed October 28, 2021, https://www.bls.gov/ooh/office-and-administrative-support/police-fire-and-ambulance-dispatchers.htm

[2] These entities are referred to by some as Public Safety Answering Points (PSAPs).

[3] National Emergency Number Association, “9-1-1 Statistics,” accessed November 22, 2021, https://www.nena.org/page/911Statistics.

[4]APCO International, “Project RETAINS: Staffing and Retention in Public Safety Answering Points (PSAPs): A Supplemental Study,” 2017, https://www.apcointl.org/services/staffing-retention/; C. Scott, “911 Has Its Own Emergency: Not Enough Call Takers and Dispatchers,” KDVR, May 24, 2021, https://kdvr.com/news/local/not-enough-911-call-takers-and-dispatchers/.

[5] APCO International, “Project RETAINS.”

[6] Rachel Cardin, “911 Calls Surge With COVID-19 Cases, Thinly Staffed Firefighters Struggle To Keep Up,” CBS Baltimore, November 21, 2021, https://baltimore.cbslocal.com/2021/12/27/911-calls-surge-with-covid-19-cases-as-firefighters-struggle-to-keep-up/; Gwynne Hogan, “NYC EMS Faces Record Staffing Shortage As 911 Calls For COVID-Like Symptoms Surge,” Gothamist, December 29, 2021, https://gothamist.com/news/nyc-ems-faces-record-staffing-shortage-911-calls-covid-symptoms-surge; Amanda Hari, “San Francisco Overwhelmed by 911 COVID-19 calls,” KRON4, January 8, 2022, https://www.kron4.com/news/bay-area/san-francisco-overwhelmed-by-911-covid-19-calls/.

[7] Lum et al., “Constrained Gatekeepers.”

[8] Lum et al., “Constrained Gatekeepers.”

[9] Melissa Reuland, “A Guide to Implementing Police-based Diversion Programs for People with Mental Illness,” Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration GAINS Center – Technical Assistance and Policy Analysis Center for Jail Diversion, 2004, https://perma.cc/LGM2-9S6G.

[10] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Outlook Handbook,” September 15, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/.

[11] S. Rebecca Neusteter et al., “Understanding Police Enforcement: A Multicity 911 Analysis,” Vera Institute of Justice, September 2020, https://www.vera.org/publications/understanding-police-enforcement-911-analysis.

[12] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Occupational Outlook Handbook.”

[13] Heidi Kevoe-Feldman and Anita Pomerantz, “Critical timing of actions for transferring 911 calls in a wireless call center,” Discourse Studies 20, no. 4 (2018): 488-505; Balakrishan S. Manoj and Alexandra Hubenko Baker, “Communication challenges in emergency response,” Communications of the ACM 50, no. 3 (2007): 51-53, https://doi.org/10.1145/1226736.1226765.

[14] Roberta Mary Troxell, “Indirect exposure to the trauma of others: The experiences of 9-1-1 telecommunicators,” (PhD diss., University of Illinois at Chicago, 2008), https://uic.figshare.com/account/projects/71123/articles/10898648.

[15] Roge Karma, “Want to fix policing? Start with a better 911 system,” Vox, August 10, 2020, https://www.vox.com/2020/8/10/21340912/police-violence-911-emergency-call-tamir-rice-cahoots.

[16] Don H. Zimmerman, “Talk and its Occasion: The Case of Calling the Police,” in Meaning, Form and Use in Context: Linguistic Applications, ed. D. Schiffrin (Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press, 1984): 210-228.

[17] Don H. Zimmerman, “The Interactional Organization of Calls for Emergency Assistance,” in Talk at Work: Social Interaction in Institutional Settings, ed. P. Drew & J. Heritage (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 418.

[18] Angela Cora Garcia and Penelope Ann Parmer. “Misplaced mistrust: The collaborative construction of doubt in 911 emergency calls.” Symbolic Interaction 22, no. 4 (1999): 297-324.

[19]Isabel Gardett et al., “Past, Present, and Future of Emergency Dispatch Research: A Systematic Literature Review,” Annals of Emergency Dispatch & Response 29 (2016): 29-42, https://perma.cc/SQ3N-DEQW; S. Rebecca Neusteter et al., “Understanding Police Enforcement.”.

[20]Jessica W. Gillooly, “How 911 callers and call‐takers impact police encounters with the public: The case of the Henry Louis Gates Jr. arrest,” Criminology & Public Policy 19, no. 3 (2020): 787-804, https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12508.

[21]Jessica W. Gillooly, “Police Encounters.”

[22] Industry Council for Emergency Response Technologies (iCERT), History of 911 and What It Means for the Future of Emergency Communications (Washington, DC: iCERT, 2015), 3, https://perma.cc/YL97-9J9C.

[23] Gardett et al., “Past, Present, and Future.”

[24] iCERT, “History of 911.”

[25] National Emergency Number Association PSAP Operations Committee 9-1-1 Call Processing Working Group, “NENA Standard for 9-1-1 Call Processing,” April 16, 2020,

https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.nena.org/resource/resmgr/standards/nena-sta-020.1-2020_911_call.pdf.

[26] APCO International, “Guidecards,” accessed December 3, 2021, https://www.apcointl.org/services/guidecards/.

[27] Jeff. J. Clawson, “The DNA of Dispatch: The Reasons for a Unified Medical Dispatch Protocol,” Journal of Emergency Medical Services, 1997, https://perma.cc/5X87-4QQ9; Neusteter et al., “Understanding Police Enforcement.”

[28] 911.gov, “Telecommunicators & Training,” accessed December 3, 2021, https://www.911.gov/issue_telecommunicatorsandtraining.html.

[29] 911.gov, “Telecommunicators & Training.”

[30] 911.gov, “National 911 Annual Report 2019,” 2020, https://www.911.gov/pdf/National_911_Annual_Report_2019_Data.pdf.

[31] 911.gov, “National 911 Annual Report 2019.”

[32] North Carolina Department of Justice, “Minimum Training Standards: Telecommunicators,” NC DOJ, September 5, 2019, https://ncdoj.gov/law-enforcement-training/sheriffs/training-requirements/minimum-training-standards-telecommunicators/.

[33] North Carolina Department of Justice, “Minimum Training Standards: Telecommunicators.”

[34] Pew Charitable Trusts, “911 Call Centers Lack Resources to Respond to Behavioral Health Crises,” 2021, https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2021/11/911-call-centers-lack-resources-to-handle-behavioral-health-crises.pdf.

[35] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Outlook: Public Safety Telecommunicators.”

[36] ZipRecruiter, “Q: What Is the Average 911 Dispatcher Salary by State in 2021?,” accessed December 3, 2021, https://www.ziprecruiter.com/Salaries/What-Is-the-Average-911-Dispatcher-Salary-by-State.

[37] Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Outlook: Public Safety Telecommunicators.”

[38] APCO International, “Project RETAINS.”

[39] APCO International, “Project RETAINS.”

[40] RadioResource International, “Public Safety Groups Disappointed with OMB Decision not to Reclassify Telecommunicators,” November 29, 2017, https://www.rrmediagroup.com/News/NewsDetails/NewsID/16275/.

[41] Andrea Fox, “House Passes 911 Dispatcher Reclassification,” Gov1, July 18, 2019, https://www.gov1.com/public-safety/articles/house-passes-911-dispatcher-reclassification-ZfQcPEwENt43G6m2/.

[42] Laura French, “Legislators Reintroduce Bill to Change Job Classification of 911 Dispatchers Nationwide,” EMS1, April 1, 2021, https://www.ems1.com/communications-dispatch/articles/legislators-reintroduce-bill-to-change-job-classification-of-911-dispatchers-nationwide-ujPF8hi3WCbVIJcR/.

[43] APCO International, “Project RETAINS.”

[44] Bo Brismar et al., “Training of Emergency Dispatch-Center Personnel in Sweden,” Critical Care Medicine 12, no. 8 (1984): 679-680, https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-198408000-00017.

[45] Paul A. Calle et al., “Do Victims of an Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Benefit from a Training Program for Emergency Medical Dispatchers?,” Resuscitation 35, no. 3 (1997): 213-218.

[46] Gardett et al., “Past, Present, and Future.”

[47] Lum et al., “Constrained Gatekeepers.”

[48] Jessica W. Gillooly, “‘Lights and Sirens:’ Variation in 911 Call‐Taker Risk Appraisal and its Effects on Police Officer Perceptions at the Scene,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management (December 2021), https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22369

[49] Gillooly, “Lights and Sirens.”

[50] Gillooly, “Lights and Sirens.”

[51] Zimmerman, “Talk and its Occasion.”

[52] Zimmerman, “Interactional Organization.”

[53] Gillooly, “Lights and Sirens.”

[54] Gillooly. “Police Encounters.”

[55] M.R. Whalen & D.H. Zimmerman, “Describing Trouble: Practical Epistemology in Citizen Calls to the Police,” Language in Society 19, no. 4, 465–492. doi:10.1017/S0047404500014779.

[56] Garcia and Parmer, “Misplaced Mistrust.”

[57]Michaela Flippin et al., “The Effect of Procedural Injustice During Emergency 911 Calls: A Factorial Vignette-based Study,” Journal of Experimental Criminology 15, no. 4 (2019): 651–660 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-019-09369-y; Megan Quattlebaum, et al., “Principles of Procedurally Just Policing,” The Justice Collaboratory at Yale Law School, January, 2018, https://law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/area/center/justice/principles_of_procedurally_just_policing_report.pdf.

[58] Erik C. Cerbulis, “Job Attitudes of 911 Professionals: A Case Study of Turnover Intentions and Concerns Among Local Governments Throughout Central Florida,” Masters thesis, University of Central Florida (2001): 225. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/225.

[59] Michelle M. Lilly and Heather Pierce, “PTSD and Depressive Symptoms in 911 Telecommunicators: The Role of Peritraumatic Distress and World Assumptions in redicting risk,” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 5, no. 2 (2013): 135-141, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026850.

[60] Heather Pierce and Michelle M. Lilly, “Duty-related Trauma Exposure in 911 Telecommunicators: Considering the Risk for Posttraumatic Stress,” Journal of Traumatic Stress 25, no. 2 (2012): 211-215. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21687; Michelle M. Lilly and Christy E. Allen, “Psychological Inflexibility and Psychopathology in 9‐1‐1 Telecommunicators,” Journal of Traumatic Stress 28, no. 3 (2015): 262-266.

[61] Dana Marie Dillard, “The Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping: Predicting Posttraumatic Distress in Telecommunicators,” PhD diss., Walden University (2019), https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/6719/.

[62]Elizabeth Belmonte et al., “The Impact of 911 Telecommunications on Family and Social Interactions,” Gov1, February 5, 2020, https://www.gov1.com/emergency-management/articles/the-impact-of-911-telecommunications-on-family-and-social-interactions-t4fHEXWZMJCLfPdz/.

[63] Troxell, “Indirect Exposure to Trauma.”

[64] Lilly and Allen, “Psychological Inflexibility;” Sandra L Ramey et al., “Evaluation of Stress Experienced By Emergency Telecommunications Personnel Employed in a Large Metropolitan Police Department,” Workplace Health & Safety 65, no. 7 (2017): 287-294; Cheryl Regehr et al., “Predictors of Physiological Stress and Psychological Distress in Police Communicators,” Police Practice and Research 14, no. 6 (2013): 451-463.

[65] Tod. W. Burke, “Dispatcher Stress and Job Satisfaction,” in Protect Your Life: A Health Handbook for Law Enforcement Professionals, ed. Davidson C. Umeh (Rockville: Looseleaf Law Publications, 1999), 79-86, https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Photocopy/143957NCJRS.pdf.

[66] Benjamin Trachik et al., “Is Dispatching to a Traffic Accident as Stressful as Being in One? Acute Stress Disorder, Secondary Traumatic Stress, and Occupational Burnout in 911 Emergency Dispatchers,” Annals of Emergency Dispatch & Response 3, No. 3 (2015): 27-38, https://www.aedrjournal.org/is-dispatching-to-a-traffic-accident-as-stressful-as-being-in-one-acute-stress-disorder-secondary-traumatic-stress-and-occupational-burnout-in-911-emergency-dispatchers.

[67] Malcolm J. Harrington, “Health Effects of Shift Work and Extended Hours of Work.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 58, no. 1 (2001): 68-72; Kate Sparks et al., “The Effects of Hours of Work on Health: a Meta‐Analytic Review,” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 70, no. 4 (1997): 391-408, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00656.x.

[68] Michelle M. Lilly et al., “Predictors of Obesity and Physical Health Complaints Among 911 Telecommunicators,” Safety and Health at Work 7, no. 1 (2016): 55-62, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2015.09.003.

[69]Hendrika Meischke et al., “An Exploration of Sources, Symptoms and Buffers of Occupational Stress in 9-1-1 Emergency Call Centers,” Annals of Emergency Dispatch and Response 3, no. 2 (2015): 28-35, https://www.aedrjournal.org/an-exploration-of-sources-symptoms-and-buffers-of-occupational-stress-in-9-1-1-emergency-call-centers.

[70] Lilly et al., “Predictors of obesity;” Lilly and Pierce, “PTSD in 911 telecommunicators;” Pierce and Lilly, “Trauma Exposure in Telecommunicators.”

[71] Dillard, “Predicting Posttraumatic Distress in Telecommunicators.”

[72] Gardett et al., “Past, Present, and Future.”

[73] Gardett et al., “Past, Present, and Future.”

References

911.gov. “Telecommunicators & Training.” Accessed December 3, 2021. https://www.911.gov/issue_telecommunicatorsandtraining.html.

911.gov. “National 911 Annual Report: 2019 Data.” 2020. https://www.911.gov/pdf/National_911_Annual_Report_2019_Data.pdf

APCO International. “Guidecards.” Accessed December 3, 2021. https://www.apcointl.org/services/guidecards/.

APCO International. “Minimum Training Standards for Public Safety Telecommunicators.” 2015. https://perma.cc/752L-2HFJ.

APCO International. “Staffing & Retention.” Accessed December 3, 2021. https://www.apcointl.org/services/staffing-retention/.

Belmonte, Elizabeth, Anne Camaro, D. Jeremy Demar, and Adam Timm. “The Impact of 911 Telecommunications on Family and Social Interactions.” Gov1 by Lexipol. February 5, 2020. https://www.gov1.com/emergency-management/articles/the-impact-of-911-telecommunications-on-family-and-social-interactions-t4fHEXWZMJCLfPdz/.

Brismar, Bo, Bengt-Einar Dahlgren, Jarl Larsson. “Training of Emergency Dispatch-center Personnel in Sweden.” Critical Care Medicine 12, no. 8 (1984): 679-680. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003246-198408000-00017.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. “Occupational Outlook Handbook.” September 15, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. “Occupational Outlook Handbook: Public Safety Telecommunicators.” Accessed November 24, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/office-and-administrative-support/police-fire-and-ambulance-dispatchers.htm.

Burke, Tod W. “Dispatcher Stress and Job Satisfaction.” In Protect Your Life: A Health Handbook for Law Enforcement Professionals, edited by Davidson C. Umeh, 79-86. Rockville: Looseleaf Law Publications, 1999. https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/Photocopy/143957NCJRS.pdf.

Calle, Paul A., Linda Lagaert, Omer Vanhaute, and Walter A. Buylaert. “Do Victims of an Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Benefit from a Training Program for Emergency Medical Dispatchers?” Resuscitation 35, no. 3 (1997): 213-218. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0300-9572(97)00058-0.

Cardin, Rachel. “911 Calls Surge With COVID-19 Cases, Thinly Staffed Firefighters Struggle To Keep Up.” CBS Baltimore, November 21, 2021. https://baltimore.cbslocal.com/2021/12/27/911-calls-surge-with-covid-19-cases-as-firefighters-struggle-to-keep-up/.

Cerbulis, Erik C., “Job Attitudes of 911 Professionals: A Case Study of Turnover Intentions and Concerns Among Local Governments Throughout Central Florida.” Honors Thesis, University of Central Florida, 2001. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/225.

Clawson, Jeff J. “The DNA of Dispatch: The Reasons for a Unified Medical Dispatch Protocol,” Journal of Emergency Medical Services 22, (5):55-7 (1997).

Dillard, Dana Marie. “The Transactional Theory of Stress and Coping: Predicting Posttraumatic Distress in Telecommunicators.” PhD diss., Walden University, 2019. https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations/6719/.

Flippin, Michaela, Michael D. Reisig, Rick Trinkner. “The Effect of Procedural Injustice During Emergency 911 Calls: A Factorial Vignette-based Study.” Journal of Experimental Criminology 15, no. 4 (2019): 651–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-019-09369-y.

Fox, Andrea. “House Passes 911 Dispatcher Reclassification.” Gov1 by Lexipol. July 18, 2019. https://www.gov1.com/public-safety/articles/house-passes-911-dispatcher-reclassification-ZfQcPEwENt43G6m2/.

French, Laura. “Legislators Reintroduce Bill to Change Job Classification of 911 Dispatchers Nationwide.” EMS1. April 1, 2021. https://www.ems1.com/communications-dispatch/articles/legislators-reintroduce-bill-to-change-job-classification-of-911-dispatchers-nationwide-ujPF8hi3WCbVIJcR/.

Garcia, Angela Cora, and Penelope Ann Parmer. “Misplaced Mistrust: The Collaborative Construction of Doubt in 911 Emergency Calls.” Symbolic Interaction 22, no. 4 (1999): 297–324. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1016/S0195-6086(00)87399-3.

Gardett, Isabel, Jeff Clawson, Greg Scott, Tracey Barron, Brett Patterson, and Christopher Olola. “Past, Present, and Future of Emergency Dispatch Research: A Systematic Literature Review.” Annals of Emergency Dispatch & Response 1, no. 2 (2013): 29-42. https://emj.bmj.com/content/33/9/e4.1.

Gillooly, Jessica W. “How 911 Callers and Call-takers Impact Police-Civilian Encounters: The Case of the Henry Louis Gates Jr. Arrest.” Criminology & Public Policy 19, no. 3 (2020): 787–804. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12508.

Hari, Amanda. “San Francisco Overwhelmed by 911 COVID-19 calls.” KRON4. January 8, 2022. https://www.kron4.com/news/bay-area/san-francisco-overwhelmed-by-911-covid-19-calls/.

Harrington, Malcolm J. “Health Effects of Shift Work and Extended Hours of Work.” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 58, no. 1 (2001): 68-72. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/oem.58.1.68.

Henry, Dan. “NENA Members Making a Difference in Fight for Reclassification, but There’s More to Be Done.” The Call. Accessed December 3, 2021. https://www.thecall-digital.com/nenq/0219_issue_32/MobilePagedArticle.action?articleId=1495182.

Hogan, Gwynne. “NYC EMS Faces Record Staffing Shortage As 911 Calls For COVID-Like Symptoms Surge.” Gothamist. December 29, 2021. https://gothamist.com/news/nyc-ems-faces-record-staffing-shortage-911-calls-covid-symptoms-surge

Industry Council for Emergency Response Technologies (iCERT), “History of 911 and What It Means for the Future of Emergency Communications.” Accessed December 5, 2021. https://perma.cc/YL97-9J9C.

Karma, Roge. “Want to fix policing? Start with a better 911 system.” Vox. August 10, 2020. https://www.vox.com/2020/8/10/21340912/police-violence-911-emergency-call-tamir-rice-cahoots.

Kevoe-Feldman, Heidi, and Anita Pomerantz. “Critical Timing of Actions for Transferring 911 Calls in a Wireless Call Center.” Discourse Studies 20, no. 4 (2018): 488-505. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461445618756182.

Lilly, Michelle M., and Heather Pierce. “PTSD and Depressive Symptoms in 911 Telecommunicators: The Role of Peritraumatic Distress and World Assumptions in Predicting Risk.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5 (2012): 135-141. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026850.

Lilly, Michelle M., Melissa J. London, and Mary C. Mercer. “Predictors of Obesity and Physical Health Complaints Among 911 Telecommunicators.” Safety and Health at Work 7, no. 1 (2016): 55-62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.shaw.2015.09.003.

Lum, Cynthia, Christopher S. Koper, Megan Stoltz, Michael Goodier, William Johnson, Heather Prince; Xiaoyun Wu. “Constrained Gatekeepers of the Criminal Justice Footprint: A Systematic Social Observation Study of 9-1-1 Call-takers and Dispatchers.” Justice Quarterly 37, no. 7 (2020): 1176-1198, https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2020.1834604.

Manoj, Balakrishnan S., and Alexandra Hubenko Baker. “Communication Challenges in Emergency Response.” Communications of the ACM 50, no. 3 (2007): 51-53. https://doi.org/10.1145/1226736.1226765.

Meischke, Hendrika, Ian Painter, Michelle Lilly, Randal Beaton, Debra Revere, Becca Calhoun, and J. Baseman. “An Exploration of Sources, Symptoms and Buffers of Occupational Stress in 9-1-1 Emergency Call Centers.” Annals of Emergency Dispatch & Response 3, no. 2 (2015): 28-35. https://www.aedrjournal.org/an-exploration-of-sources-symptoms-and-buffers-of-occupational-stress-in-9-1-1-emergency-call-centers.

National Emergency Number Association PSAP Operations Committee 9-1-1 Call Processing Working Group. “NENA Standard for 9-1-1 Call Processing.” April 16, 2020. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.nena.org/resource/resmgr/standards/nena-sta-020.1-2020_911_call.pdf.

Neusteter, S. Rebecca, Maris Mapolski, Mawia Khogali, and Megan Toole. “The 911 Call Processing System: A Review of the Literature as it Relates to Policing.” Vera Institute of Justice. July 2019. https://www.vera.org/publications/911-call-processing-system-review-of-policing-literature.

Neusteter, S. Rebecca, Megan O’Toole, Mawia Khogali, Abdul Rad, Frankie Wunschel, Sarah Scaffidi, Marilyn Sinkewicz, et al. “Understanding Police Enforcement: A Multicity 911 Analysis.” Vera Institute of Justice. September 2020. https://www.vera.org/publications/understanding-police-enforcement-911-analysis.

North Carolina Department of Justice. “Minimum Training Standards: Telecommunicators.” NC DOJ. September 5, 2019. https://ncdoj.gov/law-enforcement-training/sheriffs/training-requirements/minimum-training-standards-telecommunicators/.

Pierce, Heather, and Michelle M. Lilly. “Duty-related Trauma Exposure in 911 Telecommunicators: Considering the Risk for Posttraumatic Stress.” Journal of Traumatic Stress 25, no. 2 (2012) 211-215. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.21687.

Pew Charitable Trusts. “New Research Suggests 911 Call Centers Lack the Resources to Handle Behavioral Health Crises.” October 2021. https://www.pewtrusts.org/-/media/assets/2021/10/mjh911callcenter_final.pdf.

Quattlebaum, Megan, Tracey Meares, Tom Tyler, “Principles of Procedurally Just Policing.” The Justice Collaboratory at Yale Law School. January, 2018. https://law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/area/center/justice/principles_of_procedurally_just_policing_report.pdf

RadioResource International. “Public-Safety Groups Disappointed with OMB Decision Not to Reclassify Telecommunicators.” November 29, 2017. https://www.rrmediagroup.com/News/NewsDetails/NewsID/16275/.

Ramey, Sandra L., Yelena Perkhounkova, Maria Hein, Sophia J. Chung, and Amanda A. Anderson. “Evaluation of Stress Experienced by Emergency Telecommunications Personnel Employed in a Large Metropolitan Police Department.” Workplace Health & Safety 65, no. 7 (2017): 287-294, https://doi.org/10.1177/2165079916667736.

Regehr, Cheryl, Vicki R. LeBlanc, Irene Barath, Janet Balch, and Arija Birze. “Predictors of Physiological Stress and Psychological Distress in Police Communicators.” Police Practice and Research 14, no. 6 (2013): 451-463, https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2012.736718.

Reuland, Melissa. “A Guide to Implementing Police-based Diversion Programs for People with Mental Illness.” Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration GAINS Center – Technical Assistance and Policy Analysis Center for Jail Diversion. January 2004. https://perma.cc/LGM2-9S6G.

Sparks, Kate, Cary Cooper, Yitzhak Fried, and Arie Shirom. “The Effects of Hours of Work on Health: A Meta‐Analytic Review.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 70, no. 4 (1997): 391-408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00656.x

Trachik, Benjamin, Madeline Marks, Clint Bowers, Greg Scott, Chris Olola, and Isabel Gardett. “Is Dispatching to a Traffic Accident as Stressful as Being in One? Acute Stress Disorder, Secondary Traumatic Stress, and Occupational Burnout in 911 Emergency Dispatchers.” Annals of Emergency Dispatch & Response 3, No. 3 (2015): 27-38. https://www.aedrjournal.org/is-dispatching-to-a-traffic-accident-as-stressful-as-being-in-one-acute-stress-disorder-secondary-traumatic-stress-and-occupational-burnout-in-911-emergency-dispatchers.

Troxell, Roberta Mary. “Indirect Exposure to the Trauma of Others: The Experiences of 9-1-1 Telecommunicators.” PhD diss., University of Illinois at Chicago, January, 2008. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/36712388_Indirect_exposure_to_the_trauma_of_others_The_experiences_of_9-1-1_telecommunicators.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. “Home: Occupational Outlook Handbook.” September 15, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/.

Whalen, Marilyn R., & Don H. Zimmerman. “Describing Trouble: Practical Epistemology in Citizen Calls to the Police.” Language in Society 19, No. 4 (1990): 465–492. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/language-in-society/article/abs/describing-trouble-practical-epistemology-in-citizen-calls-to-the-police1/53A51B32371F96A6B0B12730F87AB0B4.

Zimmerman, Don H. “Talk and its Occasion: The Case of Calling the Police.” Meaning, Form, and Use in Context: Linguistic Applications (1984): 210-228. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.1020.2764&rep=rep1&type=pdf#page=224

Zimmerman, Don H., “The Interactional Organization of Calls for Emergency Assistance.” In Talk at Work: Interaction in Institutional Settings, edited by Paul Drew and John Heritage, 418–469. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

ZipRecruiter. “Q: What Is the Average 911 Dispatcher Salary by State in 2021?” Accessed December 3, 2021. https://www.ziprecruiter.com/Salaries/What-Is-the-Average-911-Dispatcher-Salary-by-State.